The Canary Girls: The workers the war turned yellow

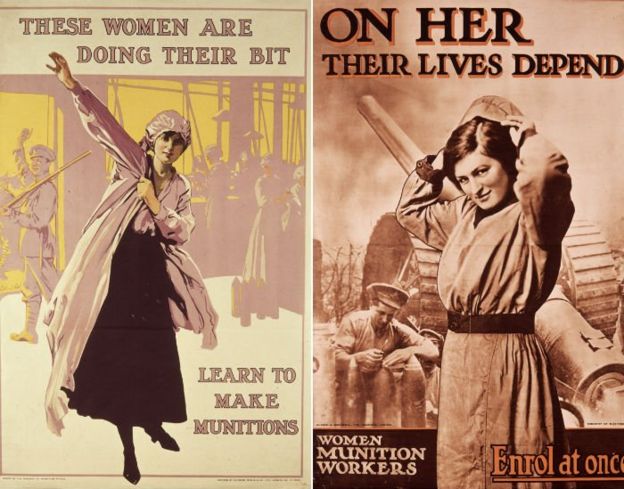

The sacrifice of soldiers killed during World Wars One and Two is well-documented. But the efforts of munitions workers stained yellow by toxic chemicals is a story much less told. A campaign now hopes to honour the so-called Canary Girls, who risked life and limb to supply ammunition to the frontline.

In 1915, while men were fighting on the battlefields, thousands of women were answering the government's cry for help by joining the war effort.

In their droves they signed up to fill the gaps left by those called into service, taking jobs in transport, engineering, mills and factories to keep the country moving.

But while those who swapped domestic life for the assembly line were spared the trauma of the trenches, their jobs were nonetheless fraught with danger.

Munitions workers battling the "shell crisis" of 1915 were prime targets for enemy fire, with sites routinely flattened by enemy bombs.

Those who were spared such a fate were no less safe, facing daily peril by handling explosive chemicals that carried the risk of them contracting potentially fatal diseases.

And for some, the effects of their work were immediately visible; a lurid shade of yellow that stained their skin and hair and earned them a nickname - the Canary Girls.

PAULA KATE

PAULA KATE

"We were like a canary," said Nancy Evans, recalling her time at the Rotherwas factory in Herefordshire during World War Two.

"We were yellow, it penetrated your skin. Your hair turned blonde and on the top of the crown was the proper colour of your hair."

Though temporary, the affects of packing shells with trinitrotoluene - more commonly known as TNT - ran more than skin-deep.

According to Dr Helen McCartney, from King's College London, some workers gave birth to "bright yellow" babies.

Gladys Sangster, whose mother worked at National Filling Factory Number 9 near Banbury, Oxford, was one of them.

"I was born [during the war] and my skin was yellow," she told the BBC. "That's why we were called Canary Babies.

"Nearly every baby was born yellow. It gradually faded away. My mum told me you took it for granted, it happened and that was it."

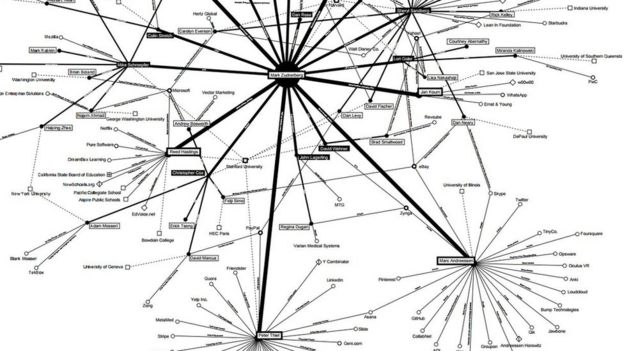

HULTON ARCHIVE

HULTON ARCHIVE

As well as suffering the cosmetic consequences of working with TNT, workers risked amputation with every shell that passed through their hands.

Amy Dale, who is researching munitions factories for her PhD, said those at Royal Ordnance Filling factories (ROFs) risked losing fingers and hands, burns and blindness.

"In these factories, they would take the casing, fill it with powder, then put a detonator in the top and that had to be tapped down. If they tapped too hard, it would detonate," she said.

"It happened to one lady, who was pregnant at the time, and it blinded her and she lost both her hands.

"She saw the pregnancy through, but the only way she could identify the baby was with her lips, which still had feeling."

HEREFORDSHIRE COUNCIL

HEREFORDSHIRE COUNCIL

Explosions were a common occurrence, with fatal blasts reported at factories in Ashton-under-Lyne, Barnbow near Leeds, and Chilwell in Nottinghamshire.

Such were fears that a rogue spark caused by static might lead to an explosion that women were banned from wearing nylon and silk.

Nellie Bagley, whose first shift at Rotherwas in 1940 was on her 18th birthday, remembers having to strip down to her underwear to be inspected.

"You took everything off and you had just your bra and if it had a metal clip on the back you couldn't wear it... and no hair grips of course, because they would caused friction... explosions."

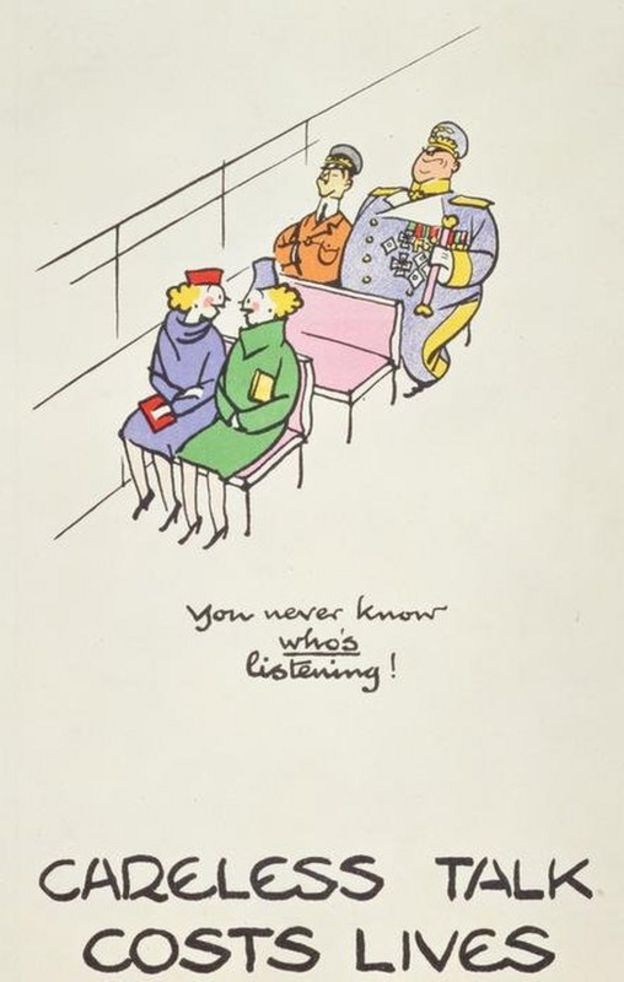

The women operated in a tense atmosphere, heavy with the weight of government fears that information could fall into the wrong hands.

Posters papered the walls bearing slogans such as "Keep Mum She's Not So Dumb" to deter talk among workers.

"They were everywhere, [the word] 'war' with a big ear on it and 'Gossip Costs Lives'," remembered Mrs Bagley.

"You were aware all the time of being watched."

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM

But even in the darkest of moments, there remained a sense of workforce camaraderie.

"When we were on nights they used to say 'Come on Lou, get us started singing'," said Louisa Jacobs, 94.

"We would sing from night to the early hours of the morning. It kept us going because we didn't realise the danger we were working in."

Fellow Rotherwas worker, Amy Hicks, added: "We would be singing, even when the bombs fell."

And fall they did. In 1942, the Rotherwas factory was attacked by the Luftwaffe, which dropped a pair of 250kg bombs on the 300-acre site.

Nancy Billings, who was coming to the end of a night shift, survived the blast.

"It was about 6am and the girl next to me had said, 'I'm so tired I could sleep forever'. Then all of a sudden the siren went off.

"This plane came down so low you could see the big black cross on it and then the bomb dropped. It had a direct hit.

"There was [numerous] girls killed in there. It always comes to me about the girl working next to me, because she was one that didn't get out."Of those who survived life in the factories, many were beset with health problems in later life.

Some reported bone disintegration, while others developed throat problems and dermatitis from TNT staining.

"The women suffered all sorts of illnesses and ailments from turning yellow, but turning yellow was probably the least of their problems," said Dr McCartney.

"They accepted all sort of terrible working conditions, they knew they were putting themselves in danger - TNT was yellow, they saw what was happening.

"But there's evidence that it was seen as a patriotic act… as them doing their bit for the war effort."

Others suffered more sinister illnesses - one of the most serious being a liver disease called toxic jaundice.

There were 400 cases of the disease during World War One - a quarter of which were fatal, said historian Anne Spurgeon.

"There was the yellow that was the staining of the skin, which while unpleasant, wasn't fatal or a serious disease.

"But there was this liver disease that was a different yellow.

"When they had repeated exposure to TNT, it attacked the liver. It was a poison and caused anaemia and jaundice."

In 1914, it was discovered TNT was poisonous and the following year, toxic jaundice became a notifiable disease.

Health and safety measures in factories were stepped up to limit exposure, such as providing protective clothing, but only so much could be done to eradicate the risks.

"[The government] wasn't ignoring it, they were trying to do something about it within the limits of their knowledge at the time," said Dr Spurgeon.

"But [TNT] was what had to go into the shells, so they had to use i

About a million women worked at thousands of Ministry of Munitions sites during both world wars.

But the number of those killed or seriously injured in the line of duty is a mystery - something Ms Dale is trying to find out as part of her research.

"It was a really dangerous job, which I think is why so little is known about it," she said.

"Women weren't allowed anywhere near a gun, yet they were filling shells in factories.

"They were actively engaged in an act of war which I think made people uncomfortable."

A campaign led by BBC Hereford and Worcester hopes to see records of how many workers died released, as well as cement the place of munitions workers in war history.

The project has already been discussed at Prime Minister's Questions and there are plans to unveil a statue at the National Arboretum in Staffordshire

But Ms Billings said she had always felt the sacrifices made by the so-called munitionettes should have been recognised.

"I do think [we] should've got a medal for what [we] did, I've always thought that. And we should've got a letter from the Queen.

"It was a very dangerous job and it affected [our] health."

For the relatives of those who worked at Rotherwas, which had 4,000 woman at its peak, recognition has been a long time coming.

"It was such a dangerous job," said Mrs Hicks's daughter, Jenny Swiffield. "It was as dangerous as going up and flying and dropping bombs.

"I'm [proud] and I think anyone would be if their parents had done something like that."

BBC