Caught in the middle of Libya's kidnapping nightmare

Kidnapping has become a growing

problem in Libya, where three governments and several militia are vying

for power. The BBC's North Africa correspondent Rana Jawad has been

talking to people personally affected.

"My father was kidnapped yesterday."

Not

quite the text message you expect to get from a close friend on a

Friday morning. I called to confirm that it was not a cruel

auto-correction and rushed over to her place. She looked remarkably

composed but exhausted.

Here, in the comfort and safety of neighbouring Tunisia, the insecurities engulfing Libya seem like a galaxy away.

She gets another call, and another, about a dozen in less than an hour.

She

stands, frowning, and clutching the phone, trying to make sense of what

was being communicated to her. She paces, kicks the kitchen chair, and

eventually sits down calmly again.

In post-revolution Libya, either armed gangs or semi-official

militias kidnap people. The motives vary, from ransom, to revenge, to

politics but the devastation and helplessness that the victims' families

experience is the same.

I saw this first-hand through my friend, Lina (not her real name).

Her

68-year-old diabetic father, university professor Salem Beitelmal, was

abducted. Six weeks on, the family is still not entirely sure which

armed group took him or why. But they have learned that his car was

found abandoned on the side of a road, west of the Libyan capital,

Tripoli.

Official statistics are not available but many Libyans I

know have either first-hand experience of being kidnapped or have had a

family member or friend abducted. Most families do not speak out,

fearing that if they go public their loved ones will be killed or

tortured in captivity.

So what happens after a kidnapping?

The

power vacuum in Libya means that in case of an emergency, you call a

friend, a neighbour, and every local militia under the Libyan sun.

At times, she looked like she was going around in circles and slowly being sucked into a vortex of misinformation.

"You don't have institutions that you can turn to that are there to protect and serve the citizens. So the reality then becomes that it is the citizens who have to take matters into their own hands," she tells me.

"But at the same time there's a strong social network that kind of replaces that, and that's how Libyans have been dealing with everything," she says.

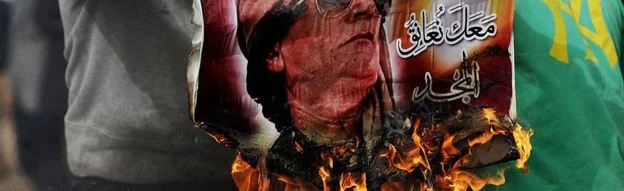

- Long-serving ruler Col Muammar Gaddafi was overthrown in October 2011

- Since then there has been no central authority

- Myriad armed militias took control of different parts of the country

- The UN has backed a government based in Tripoli

- There are two other rival governments

Kidnappings in Libya have been on the rise over the past three years.

Current

statistics are not available, but in 2015 the Libyan Red Crescent

Society reported that more than 600 people had gone missing between

February 2014 and April 2015.

No-one is immune - the victims range

from politicians to activists to businessmen to doctors to children.

And the stories are all equally tragic.

Abdel-Moez Banoun, a

high-profile anti-militia activist, disappeared from Tripoli in the late

summer of 2014 and has been deemed untraceable by human rights groups

since.

Here in Tunis, I met a young Libyan woman whose entire

family had fled their home country after a relative was kidnapped and

killed.

Jabir Zain, a young Sudanese activist who grew up in

Libya, was taken by an armed group outside a cafe in Tripoli in late

September.

It happened after he led a group discussion on women's

rights. Human rights groups have described his case as an "enforced

disappearance".

Hanan Salah, a senior researcher with the Human Rights Watch campaign

group, recently visited Libya to document cases of kidnappings. She has

been researching issues in the country for several years, but the

deteriorating security and the dangers that civilians are exposed to

still surprise her.

"I was really shocked at the normalisation of

crime, and in particular the soaring numbers of abductions for ransom,

and extortions by militias and armed gangs," she says.

She remembers one victim's story in particular.

"The

reason he was kidnapped was because the family he was being held by was

trying to pay off the ransom of another kidnapping case," she says.

Nightmare existence

What has surprised Lina the most is the realisation of just how bad things are in her country.

"If

you go to Libya today, during the day… as long as there are no clashes

in the streets, life is normal; people are going to school, to work,

shopping. Cafes and restaurants are filled.

"It gives you this false sense that there is in fact something that's keeping this country together.

"But

then when you're put into this nightmare, you realise that there are no

institutions that you can turn to, and that there is a complete

breakdown."

I ask her if she is angry.

"I'm very angry.

It angers me that we have three governments - not one - that claim power

on the ground, and the reality is that not a single one of them have

real control."

BBC NEWS